Today, experimental and commercial spaces are scattered all over the city, which has no single, centralized creative district. Some have made their way in the fast-developing downtown, a regeneration project bolstered by Quicken Loans billionaire Dan Gilbert’s real estate ventures (which are not without controversy). Others make their home in less conspicuous spaces, like a former fire engine repair shop or a long-abandoned Jeep dealership.

No matter what the backdrop, however, Detroit’s galleries have become gathering places for the city’s ever-growing collaborative community of artists and creatives. After exploring the Midwestern city’s art landscape through the inaugural Detroit Art Week, we’ve highlighted just several of the rich group of galleries the Motor City offers.

Library Street Collective

1260 Library Street, Downtown

Installation view of Nina Chanel Abney, I LEFT THREE DAYS AGO, 2016. Courtesy of Library Street Collective.

Bahamas Biennale

3106 Bellevue Street, McDougall Hunt

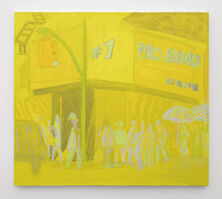

Installation view of Brook Hsu, “Fruiting Body” at Bahamas Biennale, Detroit, 2018. Courtesy of Bahamas Biennale.

Wisconsin native Sean Thomas Blott cut his teeth working in galleries across Milwaukee, St. Louis, Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles before landing in Detroit to open his own. The city’s low overhead and rich artistic community were draws. “I always wanted to grow the gallery outside of New York, because it lets me have a better quality of life—and probably allows me to be an art dealer full-time before I should be,” he said, laughing, during a recent walkthrough of his East Side space.

Blott initially operated Bahamas Biennale out of the apartments he was living in, first in Milwaukee and then Detroit. (The gallery’s cheeky, somewhat absurd name was hatched during a bleak Wisconsin winter, as Blott pondered

Maurizio Cattelan’s 2000 Caribbean Biennial project.) As Blott made more sales, he graduated to a 1,000-square-foot industrial building, and in 2017, he moved to his current location: a 107-year-old former broom factory that also had a past life as a storage facility for the auto industry.

Last May, Blott christened the space with a show of New York-based artists Joshua Citarella and Brad Troemel’s collaborative project Ultra Violet Production House, an Etsy store selling sculptures in the form of DIY kits. (Collectors buy a given artwork’s individual components, all sourced from just-in-time online shops, and are charged with assembling the work themselves.) The show debuted a delightfully idiosyncratic group of the completed pieces, including UPCYCLE planter for book you now find problematic (2017): a succulent planter forged by gouging out the center of a Terry Richardson monograph.

According to Blott, he can afford to have a largely experimental program in Detroit due to the availability of relatively inexpensive real estate. “I can produce projects here that maybe I couldn’t in New York, because the work is unsellable or just difficult,” he explained. In other words, there’s less pressure to constantly show paintings, the bread and butter for many galleries. (The current show, Brooke Hsu’s “Fruiting Body,” is the gallery’s first exhibition of canvases since landing in its new home.) In recent months, Blott has also shown the work of Detroit-based ceramics collective Hamtramck Ceramck, French sculptor Annabelle Arlie, and New York-based photographer Peter Sutherland. This fall, it will host a group show framed around the concept of relaxation.

Popps Emporium

2025 Carpenter Avenue, Hamtramck

Exterior view of Popps Packing. Courtesy of Popps Emporium.

Like many art spaces in Detroit, Popps Emporium is a multi-hyphenate operation. In the ground-floor storefront portion, a gallery hosts immersive exhibitions by local and international artists. Behind it, a communal living room, tool library, and barter board (used to facilitate trades between neighbors and friends in lieu of exchanging money) are in the works. Upstairs will eventually house a residency, while the backyard doubles as an outdoor workspace and garden, complete with composting toilet constructed by a visiting German artist.

Founding artists Faina Lerman and Graem Whyte purchased the abandoned site back in 2012, envisioning it becoming a nonprofit community space used by artists and neighbors alike. They were inspired by their own home, just across the street, which had already morphed into an exhibition space, communal workshop, and occasional site for experimental happenings and raucous parties. (Both are located in Hamtramck, a small, diverse city-within-a-city bordering Detroit’s North End that was hit particularly hard by the 2008 financial crisis). By opening Popps Emporium, the couple wanted to “formalize what was already happening in our home,” explained Lerman.

Exterior view of Popps Emporium. Courtesy of Popps Emporium.

While the space’s tool library and residency quarters are still under construction, the gallery has been up and running since 2012 and hosts projects that play with the idea of a storefront, investigating what an artistic business or social-practice project can be. Detroit-based artist Jova Lynne’s current installation transforms the storefront into a conceptual travel agency filled with tchotchkes used to promote paradise (hyper-saturated beach shots, perfectly-shaped palm trees, and big neon sunglasses abound). In this environment, Jova performs as the travel agent—helping visitors envision their ideal tropical island getaway, while also questioning the connections between tourism and the history of colonialism.

What Pipeline

3525 West Vernor Highway, Mexicantown

Installation view of Puppies Puppies, “Andrew D. Olivo 6.7.1989 – 6.7.2018” at What Pipeline, 2018. Courtesy of What Pipeline.

Michigan natives Daniel Sperry and Alivia Zivich were recent art-school grads and neighbors when they started meeting on their apartment building’s front porch to discuss the Detroit art scene. The pair saw an opportunity to present what they craved more of in the city: rigorous, experimental solo projects by emerging artists. They envisioned opening a space that would host artist-friends from the coasts and abroad, and outsiders who were curious about Detroit and wanted to make and show in the city. “We thought, ‘What can we offer?’” recalled Sperry. “‘We can help bring people here.’”

In 2013, Sperry and Zivich launched What Pipeline, a small gallery situated between a Mexican bar and an empty lot whose lone decoration is a road sign pointing north to Canada. The space’s inaugural show juxtaposed the work of Berlin-based new media artist Lucie Stahl and London-based painter Tom Humphreys; for both artists, it was their most prominent spotlight thus far in the U.S.

The gallery has since become a platform for the experimental practices of artists based within the region (Detroit’s Nolan Simon and Bailey Scieszka; Chicago-based Pope L.) and further afield (Berlin-based Henning Bohl; New York’s R. Lyon and Jessie Stead). Currently, Sperry and Zivich are showing one of their most irreverent and inspired artists, Puppies Puppies, whose work explores the intersection of the body, personal identity, and the internet. In the artist’s most overtly personal work yet, she articulates the physical and emotional strain of her recent transition from male to female. Across the space, a carpet of grass, which has browned over the course of the show, serves as the resting place for a scattering of human bones. Meanwhile, a glossy, grey granite tombstone—engraved with the artist’s name when she formerly identified as male, Andrew D. Olivo—sits solemnly at the center of the room. This fall, the gallery will present a solo project by the Detroit-born, Providence-based sculptor Michael E. Smith.

Simone DeSousa Gallery

444 West Willis Street, Midtown (Cass Corridor)

Installation view of work by Karen Azoulay, Bianca Beck, and Kyle Lockwood for “Root of the Head” at Simone DeSousa Gallery, 2018. Courtesy of Simone DeSousa Gallery.

In 1998, Simone DeSousa moved from her native Brazil to Detroit. She set up her painting practice in the city’s legendary Russell Industrial Center—the Midwest’s largest studio complex, housed within a landmarked, Albert Kahn-designed complex of warehouses. There, she found affordable space and an immensely collaborative community of artists. But over time, DeSousa realized something was missing; there weren’t enough commercial galleries to support artists with the infrastructure and sales needed to sustain and advance their work.

In 2008, DeSousa opened her namesake gallery in a former Jeep showroom in the heart of the city’s legendary Cass Corridor neighborhood. Not far from Wayne State University, the area is known for a group of avant-garde artists who lived, worked, and fraternized there in the 1960s and ’70s. Their paintings and sculptures, which have been described collectively as “Urban Expressionism,” were raw and deeply personal—a response to Detroit’s crumbling, post-industrial landscape.

DeSousa has become one of the movement’s most ardent supporters. In 2017, she organized a series of exhibitions entitled “Cass Corridor, Connecting Times,” which highlighted the work and legacy of artists like Jim Chatelain, John Egner, Nancy Pletos, and Michael Luchs (whom she represents). DeSousa also works with emerging and mid-career artists from the region and around the world; she describes her space as a “container for whatever experience an artist wants to create here.” Her current show, “Root of the Head,” juxtaposes work by Karen Azoulay, Bianca Beck, and Kylie Lockwood, each of whom addresses the physicality of the female body, and how it is articulated, perceived, and responded to.

In 2017, DeSousa also launched Edition, an adjacent storefront filled with more accessibly priced works by Detroit-based artists and designers, including print editions, unique ceramic objects, and a fantastic series of tongue-in-cheek “Lofty Bitch” coasters by Melanie Manos, which take employers to task for underpaying women. “Not everybody has $10,000 to purchase a piece, and we wanted them to feel like part of what we’re doing,” DeSousa explained, “to emphasize that they can also be collectors—they can also acquire something that is connected to the history of its maker.”

Reyes Projects

100 South Old Woodward Avenue, Birmingham

Installation view of Miles Huston, “The Style: Dweller On the Threshold” at Reyes Projects, 2018. Courtesy of Reyes Projects.

Los Angeles native Terese Reyes worked for years in galleries around Manhattan, but when it came to choosing a home for her own space, she landed on Birmingham, Michigan: a suburb that is a 20-minute drive from downtown Detroit. Reyes Projects stretches across two floors and occupies 4,600 square feet of the town’s storied Wachler Jewelry building.

Last April, the gallery’s inaugural show took full advantage of its ample footprint. Organized by Detroit-based artist Scott Reeder, “Undercover Boss” mulled contemporary social conditions like surveillance and social-media oversharing through work by Tony Cox, Sadie Laska, Jane Moseley, Jonathan Rajewski, Tyson Reeder, Greg Fadell, and others.

Tyson Reeder American, b. 1974

Reyes Projects now has 17 shows and three art fairs under its belt. It’s also brought longtime New Yorker Bridget Finn into the fold as managing director. (Previously, Finn co-founded the Brooklyn gallery Cleopatras and served as a director at Mitchell-Innes & Nash.) Together, they’ve organized delightfully smart group shows like this summer’s “Body So Delicious,” which probed the relationship between sexuality and sustenance, desire and hunger.

But solo presentations highlighting emerging and overlooked mid-career artists take precedence on the gallery’s calendar. Currently, the Detroit-born, New York-based artist LaKela Brown’s plaster reliefs of door knocker earrings and gold-capped teeth hang in the gallery’s first-floor space; they read as future fossils marking Brown’s legacy as a young black woman and the culture and commodities that surround her. This fall, Scott Reeder and New York-based sculptor Michelle Segre will take over both levels of the gallery for a two-person show.

Playground Detroit

2845 Gratiot Avenue, Eastern Market

Installation view of work by Victoria Shaheen and George Vidas for “A Difficult Pair” at PLAYGROUND DETROIT, 2018. Courtesy of PLAYGROUND DETROIT.

These days, Playground, which is located on the city’s East Side, focuses on supporting local artists. Recent shows have included Elysia Vandenbussche’s installation of miniature porcelain wall works; musician-painter SHEEFY’s bold prints inspired by the city’s nightlife; and a dual exhibition of playful, neon-accented pieces by Cranbrook grad Victoria Shaheen and Alfred University alum George Vidas(who also owns the Detroit-based artisanal neon-fabrication shop Signifier Signs).

Wasserman Projects

3434 Russell Street #502, Eastern Market

Installation view of work by Peter Zimmermann and Abigail Murray in “Color-aid” at Wasserman Projects, 2018. Photo by P.D. Rearick. Courtesy of Wasserman Projects.

The post Artsy // 8 Detroit Galleries Fueling the City’s Creative Community appeared first on PLAYGROUND DETROIT.